TL;DR: given what we know about competitive (antisocial) behaviour, I recommend taking seriously the threat of Putin deliberately creating a nuclear power plant disaster in Ukraine.

|

Too wordy, want a video? I made this one. It's less than

10 minutes, or 5 minutes if you speed it up 2x. |

I'm known mostly for my research in AI, but I only took a degree in AI because I had a competitive advantage there: I am (or was) a really good programmer. My real interest is in natural intelligence. So are two of my four higher-education degrees, and I have a number of scientific papers published in this area. (Including, contrary to what a lot of people think, that one "AI bias" paper...)

|

"You are endangering the safety of the

entire world" may be an exaggeration. |

Aside from that Science paper, one of my most-cited natural science papers is titled Explaining antisocial punishment (here's the green open access version.) Antisocial punishment (ASP) is the willingness to pay a cost to damage others who were actually helping you. Like, say, putting your conscripted soldiers in harm's way, or damaging a nuclear reactor knowing that it will contaminate your own population too, but someone else's more.

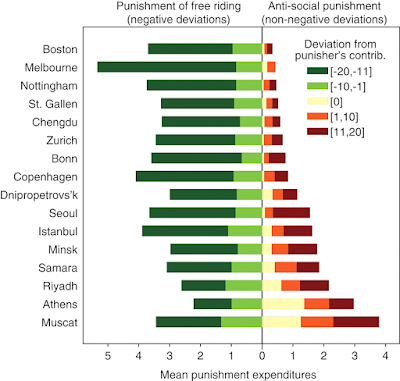

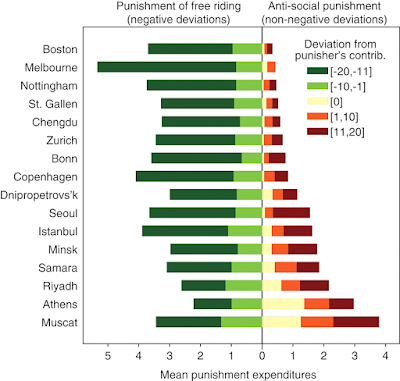

This willingness to conduct ASP is known to vary by geographic region, as you can see in this figure below from the brilliant 2008 Science article, Antisocial Punishment Across Societies. The first author of that paper is also a coauthor on my paper above, Benedikt Herrmann. Herrmann was motivated to do this study because he didn't believe that Russians would be as willing to enforce good behaviour as economists previously thought. He turned out to be right that enforcement behaviour varies by location. But he was also partly wrong: given a chance, almost everyone will punish those who don't contribute as much to public works projects as the punisher thinks people should. But in fact, people from the former Soviet Union (and the former Ottoman Empire) were way more likely than others to also punish those who gave more, or even the same amount, as they themselves did.

Since the 1990s I'd been working on a related problem. I was trying to understand whether it was "maladaptive" of people to give away information. One of the greatest mysteries for cognitive science was then seen to be why only one species (ours) had elaborated language and other technologies. A lot of people thought it was because giving away information was a bad idea, but then why did we do it? Maybe because like a peacock tail, it was costly signalling of our fitness?

|

Fig. 1 from Herrmann & al. (2008). Green is paying to punish those who contribute less to the public good than you do, which is considered altruistic. The other colours are varying degrees of antisocial.

|

But language doesn't look very much like a peacock tail. For one thing, women and children use it too. So I started learning about another explanation: maybe language and culture are forms of public goods. Since 2005 I'd had a model (with Ivana Čače) showing that indeed it was adaptive to give away knowledge, and by 2008 I knew why: because in doing so you could raise the carrying capacity of the ecosystem local to yourself. So even if you do pay a cost, you can afford to, because you and other people like you nearby have more wealth to spend. This works so long as the people near you are likely to be roughly equally as altruistic as you are, and humanity (and biology more generally) seems pretty good at making sure this is usually the case.

But in 2008, I still had two problems. First, no one believed me – I couldn't get my paper published. There was a super-popular recent paper that explained cooperation as requiring punishment to maintain. Second, if I was right, then why isn't everyone altruistic all the time? When I saw Hermann &al's paper, I knew I'd found a pathway towards answers for both. First, they'd showed that punishment wasn't only used to create altruism. What I think they've shown is that it is used either to raise or lower amounts of altruistic investment, depending on what works best in the current socioeconomic context. Second, they'd discovered some systematic variation in this behaviour. People are more likely to use antisocial punishment when they live somewhere where the GDP and rule of law are both weak. (These two features of societies tend to go together, as you might guess.)

Since finding those answers, I've succeeded in publishing a few papers in this area, like the one above, and

like the one I published last year on political polarisation. I haven't shown this yet, but I believe that political polarisation is very much akin to the propensity to antisocially punish. If I'm right, then you are more likely to antisocially punish when you can't afford to take risks, because you are in a precarious position, that is, in danger of a catastrophic loss if your well being declines too much. Cooperation is always a risk, you are depending on other people. Being more competitive is also a better strategy when you have a monopolisable resource – that is, when you can have more by excluding others. This is the contrasting situation to where you can have more by cooperating with others to construct public goods.

Why am I writing all this now, when indeed I should be working on writing grants to study exactly these questions? Because I worry that too many people find it hard to believe that Putin would jeopardise Russians' well being by creating another nuclear power plant disaster.

Putin is in a precarious position. Russia and its closest allies, Kazakhstan and Belarus, have all been experiencing democratic swings, protests, and even uprisings, as did Ukraine, particularly since he last invaded it in 2014. If he can't hold on to his form of government, he stands to lose a lot of wealth and possibly to go to jail, because he's broken a lot of laws. On the other hand, he has a lot of power which derives almost entirely through monopolisable, extractive resources: oil and gas. So by the science I just described, he seems a good candidate to consider practicing antisocial punishment – to pay a cost to lower others' positions even further.

I know there are no easy answers in this war, but my point is only this: do believe that Putin might be willing to deliberately cause a nuclear power plant disaster (or three or four), particularly if he can at all plausibly make it look like a mistake, a casualty of war, or the fault of the Ukrainians.

Comments

But, I don't believe, given the current global crises, that studies in themselves will be sufficient to navigate these challenging times. I think that there is a lot more that we can and should do in terms of relationship building among nation states with a view to helping them. I love how your research led you to discover how altruism can be a successfully adaptive behavior. I believe that we can be more altruistic toward other nations and help them to make transitions to more pan-beneficial policies and governmental institutions.

I also really appreciate your research into antisocial punishment. Not all actors are "rational actors" in the way that we have tended to use that term. Some game theory models may not apply to such actors. I would love to see more research in this area. I think that there are probably much more effective strategies leading to peaceful cooperation than tit for tat, and carrot-stick that are waiting to be discovered.

Thank you for sharing your work. It is both hopeful and inspiring!